Annotations from the Archive: Red Cloud's Founding

As we conclude restoration work on the Farmers and Merchants Bank building, we now undertake the work of reinterpreting the space to tell more of Red Cloud’s—and the National Willa Cather Center’s—story. The bank has always been a part of our guided town tour, but the renovated spaces will soon allow our guests to explore topics related to Lyra and Silas Garber, their lives and legacy in Red Cloud, and the broader history of the community.

In our organization’s early days, we were known as the Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial, and Mildred Bennett, Carrie Miner Sherwood, Jennie Reiher, and other founders took great care to preserve not only objects and papers connected with the Cather family, but also items from a number of early Webster County families. To our founders, those families—the Potters, the Ludlows, the Heffelbowers and Taylors and Jacksons, to name just a few—shared a social and historical context with the Cathers, “a kind of freemasonry,” as Willa Cather called it in My Ántonia. Their stories enhanced our understanding of Cather’s own family story, as well as the stories she herself published.

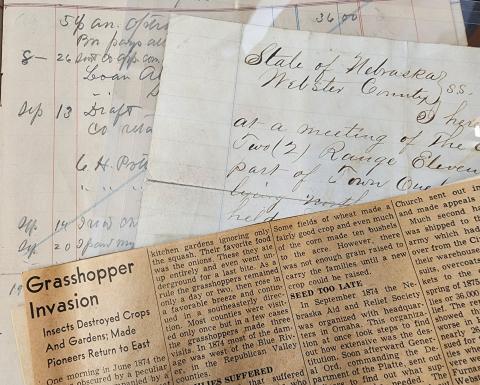

These Webster County papers were gathered from surviving family members and contain any number of fascinating stories, from the first cat in Red Cloud to the last sod house standing in the county. We haven’t had the opportunity to tell these stories fully—until now, when we can use not only the original papers, but digitized newspaper and photo archives, our mobile app, and more.

As we work to gather these anecdotes and shape them into Red Cloud’s story, enjoy a sneak preview! If you have items from Red Cloud’s history that you would like to share for our project, please contact Tracy Tucker, Director of Collections and Curation, at ttucker@willacather.org. We would love to have your support as we work to preserve these stories and the objects in our collection too! You can earmark a donation for collections when you donate on our website.

From Veda Ludlow Tennant, 1958:

It was some eighty years ago that my grandfather, William Ludlow, a retired minister, purchased our old home north of town where Herb Lambrecht now lives. . . . Having a large household he soon found out that farming could not support such a group so he turned to the making of brick. And why not? He had all the necessary material right at hand and the “know-how” he brought from his Iowa home.

The need was great in this new community for better building supplies, as sod houses were being replaced by frame structures that needed brick for chimneys and foundations. . . . The yard was a crude affair and the finished brick was a slop brick, not handsome but very durable. Later on a much better brick yard was built nearer the house but still close to the creek. . . .

The last night of [brick] firing was a gala event. Chicken was rolled in wet clay and left to roast in the hot coals, as was corn and potatoes. The women and children joined the men now at the yard and all had a good time. At other times the children, especially the girls of the family, weren’t allowed near the brick yard as the transient labor wasn’t to be trusted.

From Carrie Jackson Taylor, undated:

Before [the] machine was through threshing the grasshoppers changed toward the south that had been flying over for several days when the wind changed they began lighting & eating, the horses that were hitched on [. . . ] began [fighting] the hoppers untill they had to unhitch them. The men too were uneasy wanted to go home to see if they had visitors. That was around 4 o’clock and the next morning there was not a leaf nor kernel of corn left . . . . They ate every leaf off the potato vines, beets, cabbages, turnips, ate the onions . . . leaving holes in the ground the size of the onions. They even ate leaves of sunflowers and little peach trees. And maybe you think it wasn’t a dark outlook for people who had worked hard all summer to see all vanish in so short a time.

From David Helvern’s letter to the editor, 1875:

I think [an aid organization] in every township or road district would be very appropriate, and then there would be less discord. Now Mr. Farmer you say if you have bread don’t dabble in this aid, now that is a mistake, I have a few neighbors who have bread to eat and plenty of water to wash it down with, but how long can a man subsist on bread and water, besides you say go out and chop wood, I should like to see just such a man as you sent out to chop wood and the only food you had to be bread and water, or any other person who would misrepresent things in the grasshopper regions so as to stop the flow of aid to our suffering homesteaders.

From Julia Jackson, undated:

After the stockade was built, the first outside habitation was built by Silas Garber. It was constructed by digging a hole in the ground, then laying logs on the banks for walls, placing poles across the top and covering them with branches and sod. This dugout later became of historic importance. Governor Garber, who was a widower, lived here alone and did his own cooking. Whenever meetings were held by the settlers they were held in this dugout. The first election took place in this humble habitation; also the organization of the County took palace there. The first school ever held in the county was there and was taught by Miss Fannie Barber while the Barber family still lived in the stockade. The school began June 3rd, 1871. She was paid $12.00 a month.