Annotations from the Archive: Emil Frei Windows Are Beautiful Inside—And Out!

This autumn, as we have continued work on several of our historic sites here in Red Cloud, we had the opportunity to reach out to Emil Frei & Associates in St. Louis, and welcome Nicholas Frei—the great-great grandson of the company’s founder—to Red Cloud to examine the windows at Grace Episcopal Church. During his visits, he evaluated their condition, performed some minor repairs, and worked with our facilities team to replace the yellowed exterior storm windows, allowing the community to enjoy these beautiful windows, both inside or outside the church!

We talk about the windows often and their history as memorials to the Willa Cather’s family and friends in the church. We know the symbolism of these windows was important as well: Charles Cather’s window, for example, portrays the shepherd, significant because he had raised sheep himself in his native Virginia. The Madonna and nativity is the subject of the window dedicated to honor Willa Cather’s mother, Mary Virginia Cather. But we don’t often stop to consider how new windows for the church came to be installed at all, how the Emil Frei Art Glass Company was chosen to supply them, or the details of how they were made. That part of the story is just as fascinating!

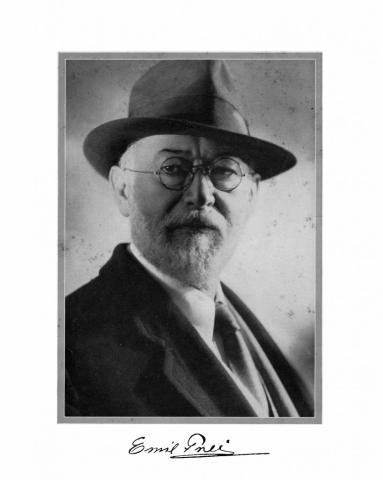

Emil Frei came to this country from his native Zoeschlingsweiler, in Bavaria. He had studied at the Munich Academy of Art before he immigrated in 1894. He and his wife Emma were in San Francisco in 1895, and finally moved back east to St. Louis, where Frei went to work designing glass murals, founding his own company in 1898 or 1899. (Emil Frei himself used both dates.)

Frei's style was known as Munich pictorial style, which is known for its romantic style and lifelike paintings of saints and biblical scenes. The pieces of glass found in windows of this type are larger than in windows of earlier styles, and details are painted atop each piece of glass before being fired and then placed inside a leaded framework.

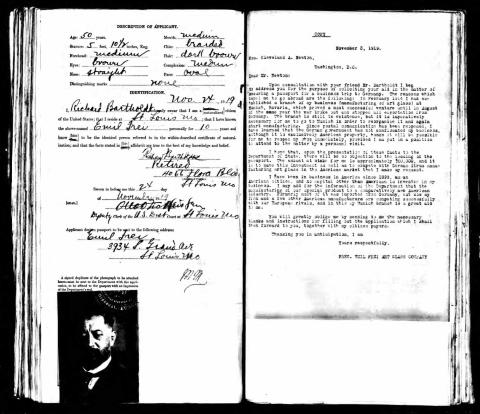

Frei's studio became known for some of the best quality stained-glass windows of this type anywhere in the world. The windows that were designed for the Holy Family Church in Watertown, New York, won the grand prize at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904, and Emil Frei found himself in high demand, particularly here in the Midwest, despite competition from designers like Louis Comfort Tiffany and John La Farge, who brought their own style and vision to stained glass. According to Nicholas Frei, the St. Louis studio was hard pressed to keep up with the work of the 1910s and 1920s, as new churches were being built at a frenzied pace to accommodate the influx of immigrants to this country, as well as being renovated and updated, as in the case of Grace Church. To meet the demand, Frei added a studio in Munich in 1914 at an investment of $20,000. Remarkably, the factory was not seized or destroyed during the World War, and Frei hurriedly applied for a passport following the war, in order to travel to Munich to reorganize and reopen the factory there.

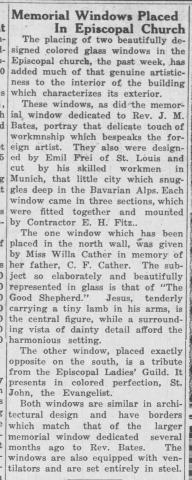

The first Cather correspondence we find regarding the Grace Church windows is Cather’s letter to Carrie Miner Sherwood, sent on June 7, 1928. Written just three months after her father’s death, Willa Cather asks for a prompt response from Mrs. Sherwood, saying that she needs the measurements for “the window for Father” and asking when she should send money for Mr. Bates’ window. The conversation, it becomes clear, has already taken place and several decisions made. Though she postpones making selections, in a June 13 letter, Cather mentions to Mrs. Sherwood that she’s pleased about the new roof on the church. It seems then, as now, the old church building was being improved and repaired! But we know from reading the newspapers in our archive that plans were underway for refurbishment of Grace Episcopal in 1925. In the Bladen Enterprise August 7, 1925 issue, it was reported that "Plans are being completed for making some notable improvements in the property of Grace Episcopal church," including a raised foundation for the addition of a basement and the west entryway expansion, installation of a furnace, and the addition of the brick veneer, still in place today. There is, however, no mention of windows!

Inspiration may have come about from a more personal request. In 1927, Cather had been asked by Carrie Miner Sherwood and her sisters to write a brief inscription for a memorial tablet to honor Mathilda Brodstone, the mother of their mutual friend, Evelyne Brodstone, otherwise known as Lady Vestey. Cather was puzzled by what type of inscription best suited such a memorial, finally telling Mary Miner Creighton that it “ought just to tell something true about her.” Cather’s inscription found a home in the dedicatory tablet for a new hospital, built by the Brodstones, in Superior, Nebraska. In January 1928, with Charles Cather again in poor health, Willa Cather returned for a long visit, and while in Red Cloud, she surprised the Superior Hospital administration by arriving for an unannounced tour.

We can only conjecture about when memorial windows entered Cather’s mind. The Brodstone memorials—which included not only a hospital but two city blocks for a bird sanctuary and a children’s park—may well have spurred Cather to consider how she would remember her own parents, when the time came. Certainly, memorial windows were in vogue at the time. St. Mark's Pro-Cathedral in Hastings was creating a memorial window for their fallen soldiers; Grant Wood was making headlines across the country for his Cedar Rapids war memorial window—considered at the time to be the largest single stained glass window in the country—a project Wood undertook with Emil Frei. Throughout the country, the newspapers were filled with advertisements for art glass studios, promoting memorial windows and marking their dedications.

Since its reopening at the close of World War I, Frei’s Munich factory was frequently mentioned in those same newspapers and periodicals (particularly Catholic ones); they made special note throughout the 1920s of the superior quality of the antique glass in Munich, the vibrancy of the windows created there, and the genius of Munich's glass artists—the very reasons that inspired Frei to open a studio there. Interestingly, the contracts drawn up for the purchase of the Grace Episcopal windows utilize much of that newspaper language exactly. The contracts were signed by Sherwood, who served as coordinator between Douglas, Elsie, and Willa Cather in the matter, and specified “the finest antique glass" and "richer and deeper colors,” as well as requesting that the windows be manufactured in Munich, rather than in St. Louis.

Further archival reading suggests that these specifications were important to the Cathers. In letters to Douglass Cather, Sherwood explains that difficulties with duties, exchange rates, and freight, have increased the cost of the memorial windows significantly yet there seems no evidence that substitutions were ever considered. Instead, Red Cloud became home to not just one, but eight of these beautifully detailed windows. In this way, Cather's love of European culture and art was brought home to Red Cloud, a tribute to her parents and old friends, and a gift to the town that inspired her so.

To learn about the 2021 restoration of these historic windows, read HERE.

Resources:

- National Archives and Records Administration

- St. Louis Modern exhibition book, by Genevieve Cortinovis

- The newspaper archives at the National Willa Cather Center and online at Newspapers.com, specifically, the Bladen Enterprise, Red Cloud Chief, Webster County Argus, and St. Louis Post-Dispatch

- The Carrie Miner Sherwood Collection at the National Willa Cather Center

- The WCPM Collection at the National Willa Cather Center

- The Irene Miner Weisz Papers at the Newberry Library

Related Articles in Our Archives:

- 1971 Spring Newsletter, Vol. 15: "Restoration," page 2

- 1971 Fall Newsletter, Vol. 15: "Restoration," page 2

- 1983 Literary Issue, Vol. 27: "Grace Church, Red Cloud: A 'True Story' of the Midwest," by the Rev. Dr. Brent Bohlke [entire issue]

- 2002 Fall Newsletter, Vol. 46: "Object Lessons: The 'Good Shepherd Window' at Grace Episcopal Church," page 44

- 2004 Winter/Spring Newsletter, Vol. 47: "Grace Episcopal Church Receives Sower Award," p. 1

- 2010 Spring Newsletter, Vol. 53: "Not Stories at All But Life Itself," by the Right Reverend Frank T. Griswold, XXV presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church, pages 60-68