Annotations from the Archive: Thornton Oakley

Any researcher can tell you about an “accident of the archives.” A misfiled photo or document may cross a researcher’s path and lead them to make new discoveries; the absence of that same document from its more logical filing place might obscure other connections. It can take years for such a situation to be discovered. Such was the circumstance in our archives when Edith Lewis’s two watercolor sketches of Grand Manan were unframed for digitization.

Each had come to our collection separately, though both originated with Willa Cather’s niece, Helen Cather Southwick. Both had come to us in their original, simple frames. One depicted the dunes of the island, while the other showed Cather’s and Lewis’s cabin tucked into the spruce and fir trees along the cliffs. A lifetime of display was evident: the watercolor paper itself was darkening, the frame had worked loose at its joints. The pieces had long been in dark archival storage, waiting for their moment to be cleaned, digitized, and rehoused—safe for another hundred years.

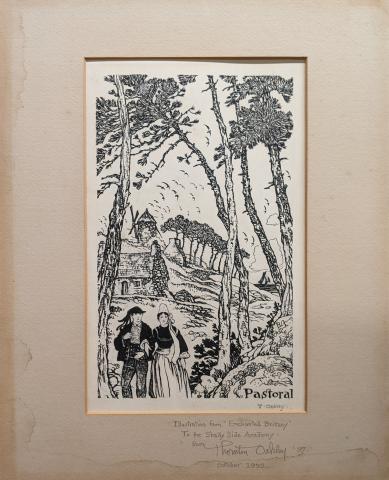

Behind the cabin scene, however, there was a surprise. Once the frayed wire hangers were removed from the frame and the cardboard backer gently lifted, another layer of artboard could be seen instead of the expected watercolor paper. When this intermediate layer was removed and turned over, an original pen and ink drawing, signed and inscribed by artist and illustrator Thornton Oakley, was revealed.

Oakley was born in 1881 in Pittsburgh; he graduated from Shady Side Academy and initially trained as an architect before studying with Howard Pyle to become a professional illustrator. He worked in graphite, pen and ink, and oil paint. Many consider Oakley’s city scenes to be his best work, focused on the scale and smoke of industrial Pittsburgh. He married Amy Ewing, a travel writer, and the couple collaborated on travel books that prominently featured Oakley's illustrations.

How does this all relate to Willa Cather, one might ask; the answer isn’t fully known—yet. We know that Cather was a fan of illustrator and teacher Howard Pyle; she had sent him an inscribed copy of The Troll Garden in 1906, referencing the Cather children's love of his illustrations. And we know that Cather was familiar with Oakley's own work. In a June 1914 letter to Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant, Cather wrote, “I think Thornton Oakley is a really big man. He once did some wonderful things of Pittsburgh and the mills. He’s never commonplace.” Surely the impetus for this letter was Sergeant's piece, “M. Le Curé’s Lunch-Party,” which was to be published in Scribner’s December 1915 issue, with illustrations by Oakley. However, Cather continued in her letter, “An illustrated book on Provence would have more ‘drive’ in the market of a motor-mad world, than a book of essays, surely.” Sergeant was, by this time, also writing for New Republic, and the sketches she was creating of French life were collected into 1916’s French Perspectives—without the illustrations that Cather suggested.

Enchanted Brittany, written by Amy Oakley and illustrated by Thornton Oakley, was published in 1930 by The Century Company. In 1932, Thornton Oakley received the Palmes d’Officier d’Academie for his work which “honored French literature or art by making them better known abroad.” The French consul, Rene Weiller, who awarded Oakley, continued, “No one could deserve it better than Mr. Oakley, who, with Mrs. Oakley, goes yearly to France. They have issued books which make better known the Pyrenees and ‘Enchanted Brittany,’ while another will deal with our beautiful Provence.” A few months later, Oakley donated one original piece from Enchanted Brittany to Shady Side. In 1936, the Oakley’s would publish The Heart of Provence, with Thornton’s charming illustrations. Thornton Oakley died in 1953.

Helen Cather Southwick, Willa Cather's niece and the last private owner of the Edith Lewis watercolor (and therefore, the Oakley pen and ink), had her own Shady Side connection but did not begin working at the school until its expansion in 1958. She worked at the academy’s middle school library for several years before moving to the high school library, where Southwick remained until her retirement.

But the larger questions remain: how did the Oakley artwork leave Shady Side, and when? Shady Side frequently exhibited artwork—from local and regional artists and collections, to be sure, but also major traveling exhibitions of abstract and modern art—a tradition they continue today. It remains unclear when or under what circumstances the Oakley illustration might have left their possession. When did Lewis create her watercolors of Grand Manan? No date or notes exist on the sketches themselves, but Melissa Homestead, in her recent book The Only Wonderful Things: The Creative Partnership of Willa Cather & Edith Lewis, notes that Lewis had long enjoyed watercolors and sketching, and letters from the early 1930s comment on the subjects Edith might choose in upcoming visits to the island. Were Lewis’s sketches framed and hanging in the cabin when Southwick took possession of it in 1965, or were they earlier gifts from Cather or Lewis? Though damage exists to both the watercolor and the pen and ink drawing, the damage is quite distinct. While the Oakley piece clearly shows evidence of water on the matboard, the watercolor does not, suggesting the pieces weren’t always together. Did Cather herself ever know Thornton Oakley, or his wife Amy?

If nothing else, the Oakley piece represents the exciting realm of art and French culture that so interested Cather and many of her closest friends. Though we may never know all of the answers to the questions posed by these two pieces, their juxtaposition suggests interesting potential connections and possibilities for future research!

Sources:

- The Betty Kort Collection at the National Willa Cather Center in Red Cloud, Nebraska.

- June 23, 1914 letter from WC to Elizabeth Shepley Sergeant, Accessed through the Complete Letters of Willa Cather at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln; original letter located in the Literary and Historical Manuscripts (MA 1602), Morgan Library and Museum in New York.

- December 1915 Scribner’s, accessed through the Internet Archive

- The Only Wonderful Things: The Creative Partnership of Willa Cather & Edith Lewis, by Melissa J. Homestead

- The University of Delaware’s Thornton and Amy Oakley Collection

- 4 Feb 1932 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “T. Oakley is Given French Academy Prize.”

- 14 Feb 1958 Pittsburgh Gazette “Shady Side Academy to Grow, Admit Girls.”

- University of Nebraska Archives, “Helen Cather Southwick”

- Richard Harris's article "Willa Cather, Howard Pyle, and "The Precious Message of Romance," from Cather Studies 11

- Thornton Oakley biography at the Normal Rockwell Museum