Annotations from the Archives: On Reappraisal

The archives are built upon the art and the science of memory. The processes used in cataloging, arranging, and caring for collections are the science; they are reproducible and logical and the end result is a logbook of objects and their condition, location, and statistics. But those data points only tell a portion of the story, and that’s where the art comes in. Every object, every paper, is a part of a web that interconnects and weaves together the lives of every person who touched the collection: not merely the subjects of the collections themselves and their families, friends, and correspondents, but the creators and curators of the collection, and their networks of colleagues and influences, too. Think of a television detective’s “crazy-wall” of evidence and yarn-linked people, places, and ideas, and you get a sense of the connections and influences at play in the archives, too.

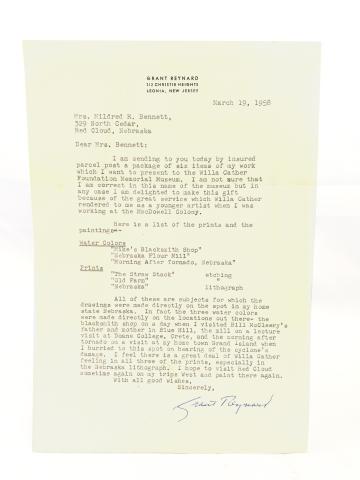

One tool of the archivist’s trade is systematic, thoughtful reappraisal. Objects and collections undergoing reappraisal are inventoried and evaluated, and their connections to the archive—their provenance, their importance to research, their value as interpretive objects—are thoughtfully considered, too. Though the process is lengthy and labor-intensive, it allows an archivist—and by extension, the archives’ users—to synthesize all the available information and really know the collection in a way that is impossible through entries on a spreadsheet. This process is underway in our collections now, as we revisit and reappraise many of the objects acquired when the Willa Cather Pioneer Memorial was a nebulous new idea, yet to be shaped. Our WCPM collection holds six pieces created by Grant Reynard (1887-1968), a Grand Island native who went on to become an illustrator, educator, painter, and poet; he studied with South Dakota painter Harvey Dunn, who had in turn studied under Howard Pyle, the illustrator who had so inspired Willa Cather as a child. Though the Reynard paintings hold a treasured place in our collections, their provenance was unclear. The answers we needed, however, were found in a recently uncovered folder of correspondence in our Mildred Bennett Collection.

In September 1947, just a few months after Willa Cather’s death, Mildred Bennett, newly settled in Red Cloud after the wartime service of her husband, Dr. Wilber K. Bennett had ended, began studying Willa Cather. During this early time she contacted many acquaintances, friends, and relatives, inquiring about their willingness to speak about the author. The Mildred Bennett Collection at the National Willa Cather Center is full of such letters, but only rarely does one elicit such an eloquent and gracious response as the letter she wrote to Grant Reynard.

“Dear Mr. Raynard [sic],” she began. “I am making a study of Willa Cather and her interest in art and artists. I understand you met her, at one time, and that you had some conversation with her. Would it be possible for me to talk with you sometime when you are out in this part of the country?”

At the time of Bennett’s letter, Reynard was engaged with the Association of American Colleges Arts Program and traveled extensively, lecturing on art while continuing to create his own paintings and sketches. His career—as a magazine illustrator and art director with publications like the Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Redbook, Good Housekeeping, Harper’s Bazaar and more—had blossomed into something bigger, and he loved giving Willa Cather much of the credit.

“Dear Mrs. Bennett,” Reynard replied. “I am sorry to have been so long in answering your letter and I will be delighted to write you a little later of a wonderful talk I had with Willa Cather years ago in New Hampshire.” He explained that he was leaving for a month of lectures in “Virginia and the South,” but had recently finished a watercolor of the Cathers’ home (the Cather Second Home on Seward Street) and visited with acquaintances of Cather’s while there.

In January 1948, Reynard returned from his lecture circuit; his recent speaking engagements, he wrote, had featured Willa Cather and the crucial suggestions that she had given him during their meeting. Before Reynard recounted his talk with Cather, he offered the watercolor painting of the Cather home to Bennett for $125, less 25% if anyone in Red Cloud wanted it. “It is one of the best paintings I have made and I have exhibited it in many colleges where of course the English departments are most interested.”

What follows formed the basis for several later published versions of Reynard’s memory of a fateful conversation with Willa Cather. A Measure of Vision (1966) recalled that afternoon, and posthumously, the Prairie Schooner published an expanded version under the title “Willa Cather’s Advice to a Young Artist.” Later still, Sharon Hoover, in her collection Willa Cather Remembered, republished the Prairie Schooner version. The letter to Bennett, however, is stripped to its essence: how Reynard met Cather, the tidbits of information he had gleaned from mutual friends, their conversation over tea. (A transcript follows, below.)

The encounter, he wrote, caused him to reevaluate everything. “I was completely lost for almost a year,” Reynard remembered, reconsidering everything from the subjects he chose to the mediums he used to depict them; eventually, Reynard said, “It percolated through my confusion that this great lady had done me a great service in talking about herself. . . . So you see the great debt which I felt I owed to Willa Cather who had uncovered the native honesty which I had smothered with much rubbish and had freed me to the great and thrilling experience of drawing and painting people and places which I really wanted to. I have been passing this experience on to students all over the country in my lectures in unending gratitude to Willa Cather.”

As Reynard’s 1972 version of the recollection states, he intended to repay this debt by presenting the watercolor of the Cather Second Home to the author in New York, but it wasn’t to be; Cather died shortly after Reynard inquired about making an appointment, and a few short months after that, he sold the painting to Mildred Bennett personally. Reynard’s correspondence with Bennett continued, however, and in 1958, he wrote, “I am sending to you today . . . six items of my work which I want to present to the Willa Cather Foundation Memorial Museum I am not sure that I am correct in this name . . . but in any case I am delighted to make this gift because of the great service which Willa Cather rendered to me as a younger artist when I was working at the MacDowell Colony.”

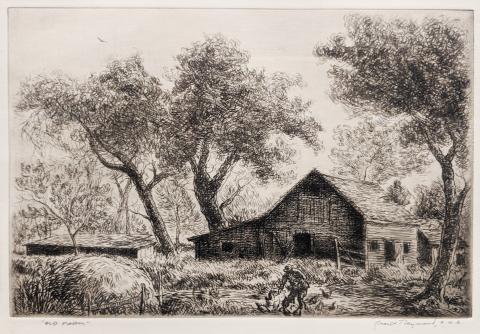

Reynard donated three watercolors, one lithograph, and two etchings to the collection. “All of these are subjects for which the drawings were made directly on the spot in my home state Nebraska. . . . I feel there is a great deal of Willa Cather feeling in all three of the prints, especially in the Nebraska lithograph. I I hope to visit Red Cloud sometime again on my trips West and paint there again.” Though much of the information contained in Reynard’s 1948 letter is collected elsewhere, it has the unpolished sincerity of an impromptu conversation; Cather’s impact on his life and career comes out in a rush of emotion that bears all the “native honesty” of Reynard’s paintings, and that tells us something new about the Reynard pieces in our collection. These weren’t purchased pieces, acquired with an intent of furnishing a room or their collectability. These were heartfelt tributes to a mentor, an acknowledgment of a debt that could never fully be repaid. Just as Cather’s words caused Reynard to re-examine his own work, Reynard’s words help us to see these six pieces in a new light, with new meaning and new relevance to our collections.

Aside from our WCPM and Mildred Bennett Collections, information was also taken from:

An American Art Colony, by Paul H. Mattingly

“Grant Reynard,” Museum of Nebraska Art

Grant Reynard's 1948 Letter

Dear Mrs. Bennett:

Thanks for your letter of Jan. 9th and I am sorry to have neglected writing you about Miss Cather. We did have a wonderful trip South and I regret that it didn’t take us through Winchester. In speaking of her in my lectures they told me in Virginia that Willa Cather had been born there. It is most interesting to me to hear about Dr. Jacks who bought a piano so many years ago from my dad. I hope sometime to talk to Dr. Jacks when I visit Nebraska. About the water color of the Cather home it is a size for which I charge $125. Of course if anyone there in Red Cloud wants it, or any civic group, I will take off 25% of that price. It is one of the best paintings I have made and I have exhibited it in many colleges where of course the English departments are most interested. By the way will you kindly send me the names of the two friends of Willa Cather with whom I had most pleasant visits—they were the Misses Minor [sic]—and I have lost their present addresses there in Red Cloud. Now that I have devoted this part of my letter to various questions I will try and tell you briefly of my meeting with Miss Cather.

The first year that I spent a period in the fall painting at the MacDowell Colony, in Peterboro, New Hampshire, Willa Cather was working on “Death Comes To the Archbishop” [sic] there. I believe this was 1926. Oddly enough I heard her speaking before I saw her. I was in the reception room at HIllcrest talking to Mrs. MacDowell when she was called to the front door where the voice which I heard told of being greatly disturbed in her writing because she had heard voices declaiming in the woods near her studio. Mrs. MacDowell assured “the voice” that no colonist was to be disturbed and that she should have her studio changed. When Mrs. MacDowell came back to me she told me that her caller was Miss Cather. It developed on investigation that the declaiming in the woods had come from a group of summer theatre actors adjacent to the colony property who had been conducting a rehearsal in the woods. After I met Willa Cather I learned that she disliked noise when writing and later a friend of mine told me that Miss Cather had rented an apartment above her own in Bank St. in New York to defend herself against noisy neighbors.

My arrival at the Colony had given me my first chance to really paint free from the need of doing other sorts of art work to make a living and I had come with great canvas and material to paint large and impressive things up there. Now feeling sure that I was really going to act like an artist I had chosen “arty” subject matter, ladies and goats, nude ladies romping with the goats through the woods, etc. Miss Cather learning that I was from Nebraska, “a fellow countryman” she called me, asked if she might drop by and see my work one day near the end of my stay. I cleaned and arranged my studio in a great dither with the great paintings hung about the place to impress her and she arrived around five one afternoon. I had tea brewing and while I got it served she wandered about the place and made no comment on my work except to praise some little drawings she found on a table. We sat down to our tea and she proceeded to talk for the rest of our visit about herself. I thought, well, this is the way with writers I suppose, but the lady knew how best to help me in telling of herself for I have never ceased to be thankful for that hour where she told me of her own career up to then. How she had lived from early youth in Nebraska, how she had come through university, on east through Chicago, Pittsburg, etc. to New York, editorial work, the gay cities, the opera, the glamour of a new life, her early writing which she said contained some attempts at “fine writing” and then how it wasn’t until she turned the carpet over and looking at the dusty back side of it remembered the little Bohemian maid (“Hired girls we called them”) who had befriended her in her early youth out in Nebraska, and rolling the curtain back she wrote in a flood of feeling about those times and days and how “My Antonia” had been a great success and how she had really found herself in relation to writing in the Nebraska novels. She said that she was convinced that the great thing was desire in art. That a desire to express ourselves be a clear compelling thing that must out, whether it be a poem, a painting, a novel, a symphony, or a piece of sculpture [sic]. No thought of editors, opinions, galleries—just a great urge to write or compose or paint coming freely through a great compelling desire. Our talk finished she left me among the ruins of my goats and ladies, a bewildered young man if there ever was one. Before long it percolated through my confusion that this great lady had done me a great service in talking about herself. I knew that I had been trying to make arty stuff, to impress committees, other artists, etc. I was completely lost for almost a year trying to decide just what I did want to draw or paint. In another year at the Colony I took a small amount of material and much humility with me and finally began to make drawings of familiar things, musical people who really interested me, then on into other fields and subjects, landscapes, trips West to my native Nebraska, the prairies, the mountains in Wyoming, the hills of New England, the characters everywhere in New York City, drawings, etchings, lithographs, water colors, paintings in oil, all subjects thrilled me, all mediums interested me, the subject was everywhere, even in my back yard. So you see the great debt which I felt I owed to Willa Cather who had uncovered the native honesty which I had smothered with much rubbish and had freed me to the great and thrilling experience of drawing and painting people and places which I really wanted to. I have been passing this experience on to students all over the country in my lectures in unending gratitude to Willa Cather.

Sincerely,

Grant Reynard